Fragmented force

Why Europe struggles with capability and readiness

Where we are now

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, European countries have dramatically increased defence spending. That surge has exposed not just the gap between what Europe has and what it needs, but a deeper and more corrosive structural weakness. According to data compiled by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, European NATO members sourced approximately 78 percent of their major new weapons systems from outside Europe between 2022 and 2024, with nearly two thirds of that total coming from the United States.1

This has happened at precisely the moment when American political commitment to European security has become less certain. In other words, as strategic dependence on Washington has grown more uncertain, industrial dependence on Washington has grown stronger.

That is not coincidence. It is the consequence of how European defence has been organised for decades.

European armed forces collectively operate around 180 major weapons systems. The United States operates roughly 30.2 Europe fields 17 different types of main battle tank, including the Leopard, Leclerc, Challenger, Ariete, PT-91, and several modernised Soviet legacy designs still in service across eastern Europe. The United States fields one, the M1 Abrams.3

The same pattern repeats across the force. Europe produces three frontline combat aircraft in parallel, the Eurofighter Typhoon, the Rafale, and the Gripen. The United States produces one. European navies operate more than two dozen classes of frigates and destroyers, each with distinct combat systems, weapons fits, training pipelines, and logistics chains. The US Navy operates a small number of standardised classes at scale.4

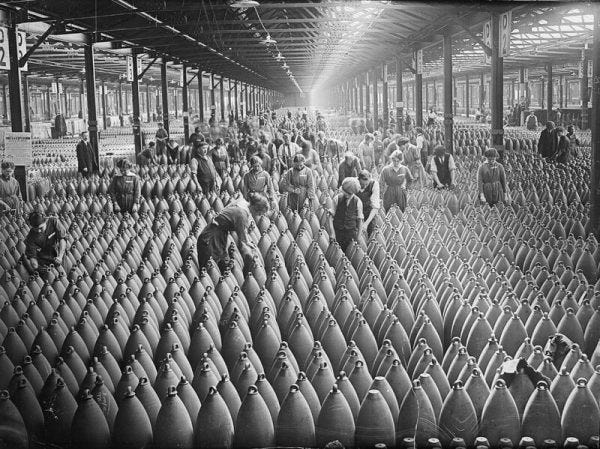

The result is European duplication on an industrial scale. Multiple design bureaux, parallel production lines, short manufacturing runs, and incompatible sustainment systems. In peacetime, this inflates costs. In war, it also constrains output.

Ukraine has made the consequences visible. Supplying Kyiv has required scavenging spare parts from across the continent, refurbishing incompatible platforms, and running parallel training programmes for weapons that perform broadly similar functions. The limiting factor has not been money but finding available kit.

How did we get here?

European defence fragmentation is not the product of incompetence. It is the product of rational national decisions that, taken together, amount to collective failure.

For most of the Cold War, defence procurement was a national responsibility. States that had recently emerged from occupation or dictatorship wanted sovereign control over weapons production for reasons that were both economic and strategic. Defence factories meant skilled jobs, regional investment, and political leverage. They also meant freedom of action. If you could build your own tanks, ships, or aircraft, you were less dependent on allies whose priorities might change.

That logic never disappeared. Even today, around 80 percent of European defence contracts are awarded to domestic suppliers.5 Governments protect local industry. Unions defend jobs. The huge defence companies lobby to keep production lines alive. From a national perspective, this is understandable. From a continental perspective, it is ruinously inefficient.

Recent events have sharpened the dilemma. Public threats by senior US political figures to reconsider America’s global commitments have forced European leaders to confront an uncomfortable reality. The strategic environment has changed, but European defence structures have not. Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2026, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney warned that the post-war order was breaking down and that “nostalgia is not a strategy.”6

The fear is not abstract. Stefano Stefanini, a former Italian ambassador to NATO, warned that a significant reduction in US military presence could cause not just NATO, but even the EU, to fragment.7 Security guarantees underpin political cohesion. When those guarantees weaken, things fall apart.

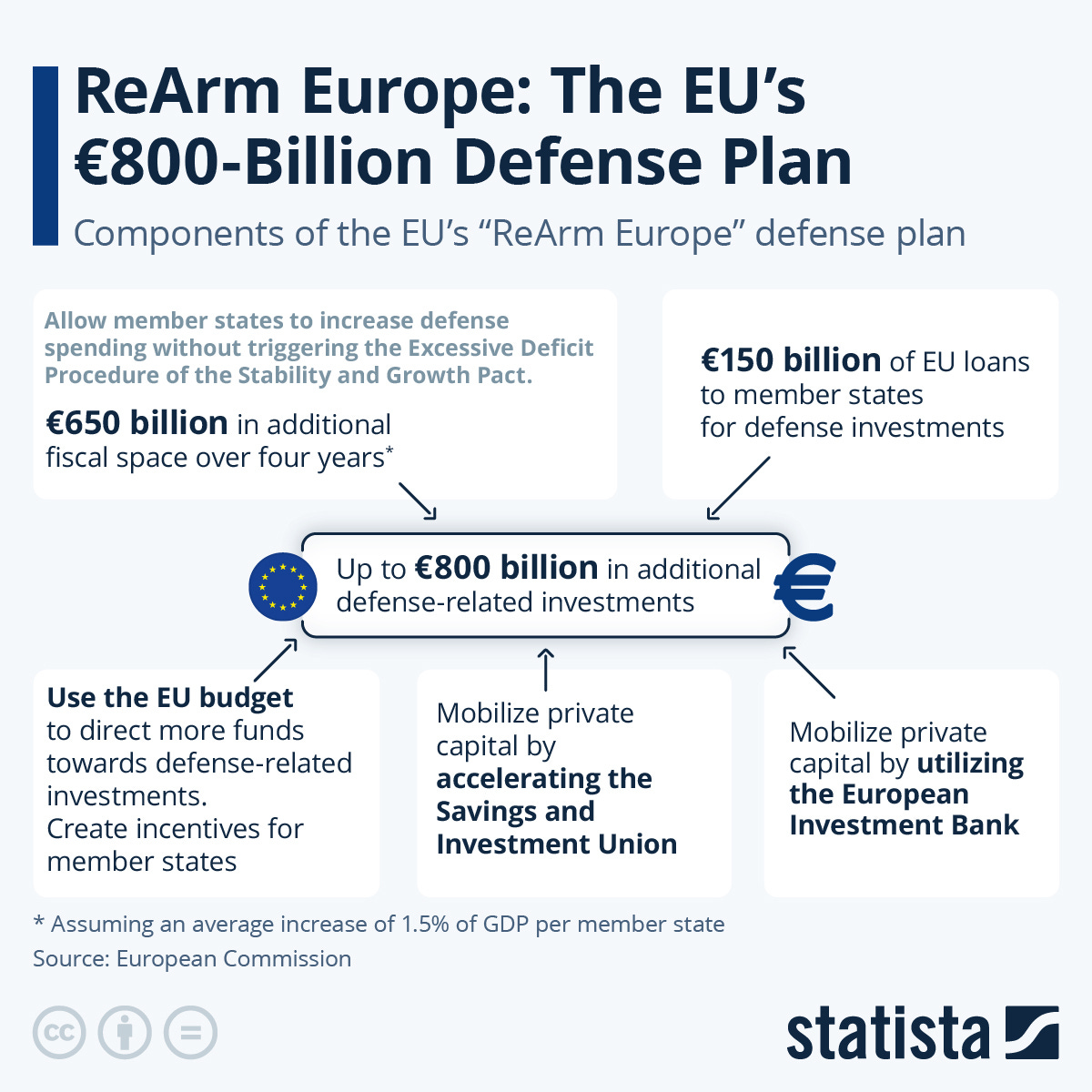

The European Union’s response has been the ReArm Europe Plan, announced in March 2025. In scale, it is unprecedented. The plan envisages up to €800 billion in additional defence-related spending by 2030, combining national fiscal flexibility, expanded European Investment Bank lending, and a new €150 billion joint loan instrument known as SAFE, the Security Action for Europe facility.8

The logic is straightforward. Countries that buy together reduce unit costs, standardise equipment, and increase output. SAFE loans are designed to incentivise joint procurement and to rebuild Europe’s industrial base at scale, particularly in ammunition, air defence, drones, and armoured vehicles.

The first tranche of SAFE funding for eight member states was approved in January 2026, with disbursements beginning in March.9 Fifteen EU states are already planning collaborative projects involving Ukraine, both to support Kyiv and to integrate its battle-tested industry into Europe’s supply chains. The EU has set an explicit target that 40 percent of defence procurement should be collaborative rather than national.

This is not about creating a European army. That idea collapses the moment it encounters reality. Allied deployments in Libya and Afghanistan demonstrated how national caveats can paralyse operations: German aircraft restricted from striking, Swedish troops limited in where they could deploy, and political vetoes exercised in real time, all exposed the limits of multinational forces without unified political authority. An army that cannot fight under pressure is not an army.

What Europe is attempting instead is to build a European defence market that can function under stress.

Britain sits awkwardly outside this structure. The UK was not offered meaningful access to SAFE but has signed a Security and Defence Partnership that allows participation in joint procurement alongside partners such as Norway and Ukraine.

Britain’s position is distinctive. Deeper participation in European procurement makes strategic sense in reducing unit costs, improving interoperability, and strengthening deterrence. But there is a powerful domestic argument. Britain’s defence sector supports hundreds of thousands of jobs directly and indirectly. Industry analysis suggests that sustained defence spending at around 3 percent of GDP could generate an additional 50,000 jobs and around £8 billion in economic value by the mid-2030s.10 Every pound spent abroad is a pound not spent in Barrow, Bristol, or Glasgow.

The same tension exists across Europe, but Britain faces it from outside the EU’s institutional framework.

Politics compounds the problem. Britain remains one of the NATO members most closely aligned with the United States. Some European officials privately describe the UK, alongside countries such as Italy, as among the most reluctant to embrace reforms perceived to dilute American influence. Negotiations over UK access to EU defence mechanisms reflect that unease. British ministers speak of agreements by mid-2027. EU officials describe that timeline as optimistic.

Yet doing nothing is itself a decision.

Europe is moving towards greater integration because fragmentation has become unaffordable. Seventeen tank variants versus one is not a slogan. It is a measure of wasted capital, constrained output, and reduced resilience in the face of war.

What can be done

First, Britain should deepen alignment with capable allies beyond purely European structures. The Global Combat Air Programme with Japan and Italy demonstrates what is possible when partners align around shared requirements, clear governance, and industrial scale. GCAP spreads development costs, accelerates innovation, and creates an exportable platform rather than a bespoke national system. It also avoids the paralysis that has plagued previous European programmes by enforcing discipline on requirements and timelines.

Second, Britain should take a leading role in capability coalitions anchored firmly in NATO. Long-range strike, integrated air and missile defence, counter-drone systems, and maritime security are areas where Britain brings real operational credibility. Coalitions that share capability without surrendering political control work. Pretend supranational armies do not.

Third, Britain must be honest about what it can and cannot do alone. We cannot build everything. We do not have the scale. But we do have areas of genuine excellence: nuclear submarines, complex warship design, jet engines, advanced sensors, and electronic warfare. The strategic task is to trade access to those strengths for access to others, not to pursue the illusion of autonomy.

Europe’s problem is not that it lacks money. It is that it lacks coherence. Fragmentation weakens deterrence. Integration, done properly, strengthens it.

Seventeen tanks versus one tells you who can fight at scale. The only remaining question is whether Europe, and Britain, chooses to learn that lesson before the next war, or during it.

Institut de relations internationales et stratégiques, The Impact of the War in Ukraine on the European Defence Market, September 2023: https://www.iris-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/19_ProgEuropeIndusDef_JPMaulny.pdf.

Statista, Europe Has Six Times as Many Weapon Systems as the U.S., February 2018: https://www.statista.com/chart/12972/europe-has-six-times-as-many-weapon-systems-as-the-us/?srsltid=AfmBOopXIP1Ou34VvHxkCe1pm9cEmBR7_OKl_ddBjyyhrwuaIAxeYRfC.

Forbes, Europe Has Six Times As Many Weapon Systems As The U.S., February 2018: https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2018/02/19/europe-has-six-times-as-many-weapon-systems-as-the-u-s-infographic/.

Modern Diplomacy, An Overview of Contemporary Naval Vessels’ Categorization, January 2025: https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2025/01/04/an-overview-of-contemporary-naval-vessels-categorization/#:~:text=But%20navies%20operating%20these%20warships,fully%20equipped%20multi%2Dmission%20capabilities.

European Centre for International Political Economy, Openness and Fragmentation in EU Defence Procurement, December 2025: https://ecipe.org/publications/openness-and-fragmentation-in-eu-defence-procurement/#:~:text=Nonetheless%2C%20defence%20contracting%20in%20the,keep%20European%20defence%20firms%20smaller.

World Economic Forum, Special address by Mark Carney, Prime Minister of Canada, January 2026: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2026/01/davos-2026-special-address-by-mark-carney-prime-minister-of-canada/.

Financial Times, NATO without America: Europe ‘thinks the unthinkable’, January 2026: https://www.ft.com/content/4e1c2056-e1be-4074-af15-5b69aed2738a.

European Parliament, ReArm Europe Plan/Readiness 2030, April 2025: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2025)769566.

European Commission, Commission approves first wave of defence funding for eight Member States under SAFE, January 2026: https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/commission-approves-first-wave-defence-funding-eight-member-states-under-safe-2026-01-15_en.

ADS Group, Increase in defence spending could deliver 50,000 new jobs by 2035 https://www.adsgroup.org.uk/knowledge/increased-defence-spending-50000-jobs/.

Logic is correct. But read EU plan as ‘French plan’.

We need clear real alliances. Not smiling enemies.

All France ever seem to do is steal our tech and pull out of any alliance. Deeply deeply unreliable. It is that endless selfishness that has underlined the problems the eu currently suffers.